- Explore Norfolk

- Beaches

- West Runton Beach

- West Runton Elephant

The West Runton Elephant

The Story Behind The Life Size Model

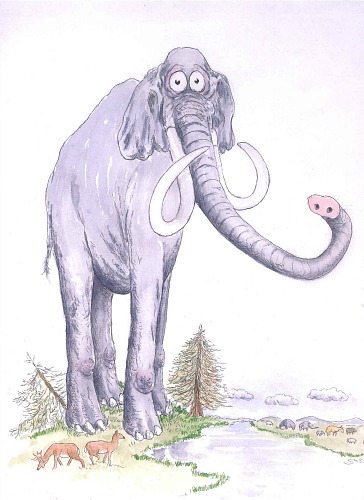

Although much has been written about the West Runton Elephant, or Mammoth to be more specific, not much is known about the extraordinary vision and subsequent creation of the articulated life size model and how it came into being. And also what the future holds for this amazing monumental discovery of bones and how it can benefit the visitors and locals of Norfolk.

The life size articulated model of the West Runton Elephant

The life size articulated model of the West Runton ElephantBut I can’t go on with any of that story until I fill you in on the fascinating discovery of what is now known as the West Runton Elephant.

The Discovery of the West Runton Elephant

Over 20 years ago now, in 1990, Margaret and Harold Hems, local residents, were walking along West Runton beach when they discovered what looked like a large bone sticking out from the cliff face. After contacting Norfolk Museums Service, it was identified as a pelvic bone of a large steppe mammoth (this bone can be seen in Norwich Castle Museum, but if you blink, you might miss it!) and nothing more was done. However, a year later, in 1991, a local fossil hunter called Rob Sinclair discovered more very large bones.

The Pelvic Bone at Norwich Castle Museum

The Pelvic Bone at Norwich Castle MuseumAs a result of these two discoveries, an exploratory excavation took place followed by a much more serious excavation which started in 1995 carried out by the Norfolk Archaelogical Unit. It took three months and during that time they managed to unearth 85% of the West Runton Elephant.

This is the most complete set of bones of a steppe mammoth that has ever been unearthed in the world. This is of major archaeological importance and this discovery, along with so many other smaller fossils which are continually discovered along this coastline, are being brought together into a tourism project to be known as the Deep History Coast project. So the future of the mammoth will live on!

At the moment the skeleton of the West Runton Elephant is hidden away at Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse Museum, but there is a small display in the two local museums, Norwich and Cromer.

However, back to the model - thanks to the vision of Suzie Lay, another local resident, she created a life size model which can show the world exactly what roamed on our North Norfolk coastline.

From the excavation of the bones, we know that the West Runton Elephant died at about the age of 42 in a fresh water river bed from a damaged femur and he would have been about 4 meters high at the shoulder and weighed about 10 tonnes. For more on the preservation of the bones, you can visit the Wikipedia website on the West Runton Elephant.

The Creation Of The West Runton Elephant Model

This is the extraordinary story of a vision, supressed for more than 5 years but which finally came to life in 2014!

The West Runton Elephant finally saw the light of day in August 2014 in front of about 750 people on the North Norfolk West Runton beach, 700,000 years after it had died, thanks to the amazingly creative mind of Suzie Lay and her engineer friend Jeremy Moore.

The Story

One day, back in 2007, Suzie was on a work bonding session at Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse Museum when they were introduced to Nigel Larkin, a palaeontologist, who, at the time, was preserving the head bones of the recently discovered mammoth. Seeing all the bones set out in this secret room which wasn’t open to the public was all Suzie needed for her creative juices to go into overdrive, and the vision of the West Runton Mammoth once again walking along the very beach where it finally came to rest was born. Nothing was going to stop her.

For five years she sat on her idea, but eventually a change in circumstances meant that she could now realise her dream.

Her first step, in her spare time, was to create a model using just four bamboo canes tied together and pushed into the ground, reaching up to a height of 4 meters (this was the height of the mammoth when alive). Not content with this model, she contacted her friend, an engineer, Jeremy Moore, to see if he’d be interested in building a life size mammoth! Not a question you get asked too often in your life I suspect!

Jeremy was well equipped to carry out the task, as his strength is finding old WWII aeroplane relics and rebuilding them to be fully operational. She thought “he builds big things, they are lightweight and they move”! Having a hanger in his back garden was also an added bonus.

|

The body is made from aeroplane plywood and laminated pine and the head from white willow. This huge life size construction was built entirely to scale with engineering drawings and takes four people to lift it up and move it. It also breaks down into various sections making it slightly easier to transport! |

|

|

Surprisingly the whole reconstruction only took about 3-4 months, but they did enlist the help of Tin House Art to build the head and the trunk. |

Once built, the next task was to make sure it could be transported as well as physically moved along the beach. The date for the reconstruction of “The West Runton Elephant Walk” was set for August 13th, so Suzie had to find 2 others to walk in its shoes. In the end, the four that made the “walk” possible were Suzie, Jeremy, Jacko and Andy. All three men are retained firemen with the Martham crew. It was watched by over 700 people, created worldwide media coverage and even trended on Twitter!

For now Hugh Mungus, as he became known, is sitting quietly in his hanger somewhere in the depths of Norfolk, waiting for some more outings in 2015. He will be appearing at "Cromer Museums at Night", at the Weybourne Festival and the Great Yarmouth Arts Festival, as well as taking another beach walk on West Runton at the end of August 2015.

Hugh Mungus, designed by Suzie Lay

Hugh Mungus, designed by Suzie LayThe life size construction is also accompanied by a very imaginative story book called “A Mammoth Adventure”, designed and written by Suzie herself, featuring Hugh Mungus, as seen above!

The future of the West Runton Elephant

In recent years the Norfolk coast has thrown up some incredibly historic finds, the mammoth skeleton being one, the 850,000 year old footprints at Happisburgh being another, as well as a whole host of other smaller pieces which has now built up a credible picture of how this Norfolk coast was once connected to the continent by land. The Norfolk coast is on what is known as the Cromer Forest-bed Formation.

As far as having a life size replica displayed in Norfolk, Norwich Museum plan to apply for a grant in order to make this a possibility. Due to the fact that the bones stored in Gressenhall are so fragile, they need to replicate the mammoth by carrying out laser scans of the skeleton and then making a 3D print of the entire mammoth. This model will then take pride of place on the ground floor of Norwich Museum for all to see.

We wait with baited breath as the Norfolk Museum Services apply for grants and funding, and with other organisations they put together what should be a fascinating project to show off these historical and important finds in Norwich, Cromer and Great Yarmouth.